Observer effect, quantum mechanics, and the need to zoom out!

Why I cant unsee it anymore..

Backbencher syndrome

In 2010, I was slouched in a quantum chemistry lecture by Prof. G. Sundar (GSu, for short), trying to wrap my head around concepts way over my capability. Let’s just say I retained barely enough to scrape through my semester exams.

Fast forward, and some of those ideas came back to haunt me—in a good way—while listening to Mukesh Bansal’s podcast with Anil Ananthaswamy and reading Through Two Doors at Once. Turns out, some of the weirdest ideas in science are also the most profound. Like the one we will talk about today, “The Observer Effect”, if you put this in ChatGPT, it shares the following definition

In quantum physics, the observer effect refers to the concept that the act of observing or measuring a quantum system alters its state. This means that simply observing a particle, such as an electron, can change how it behaves, causing it to act more like a particle than a wave.

Where it started: The Dual Nature of Matter

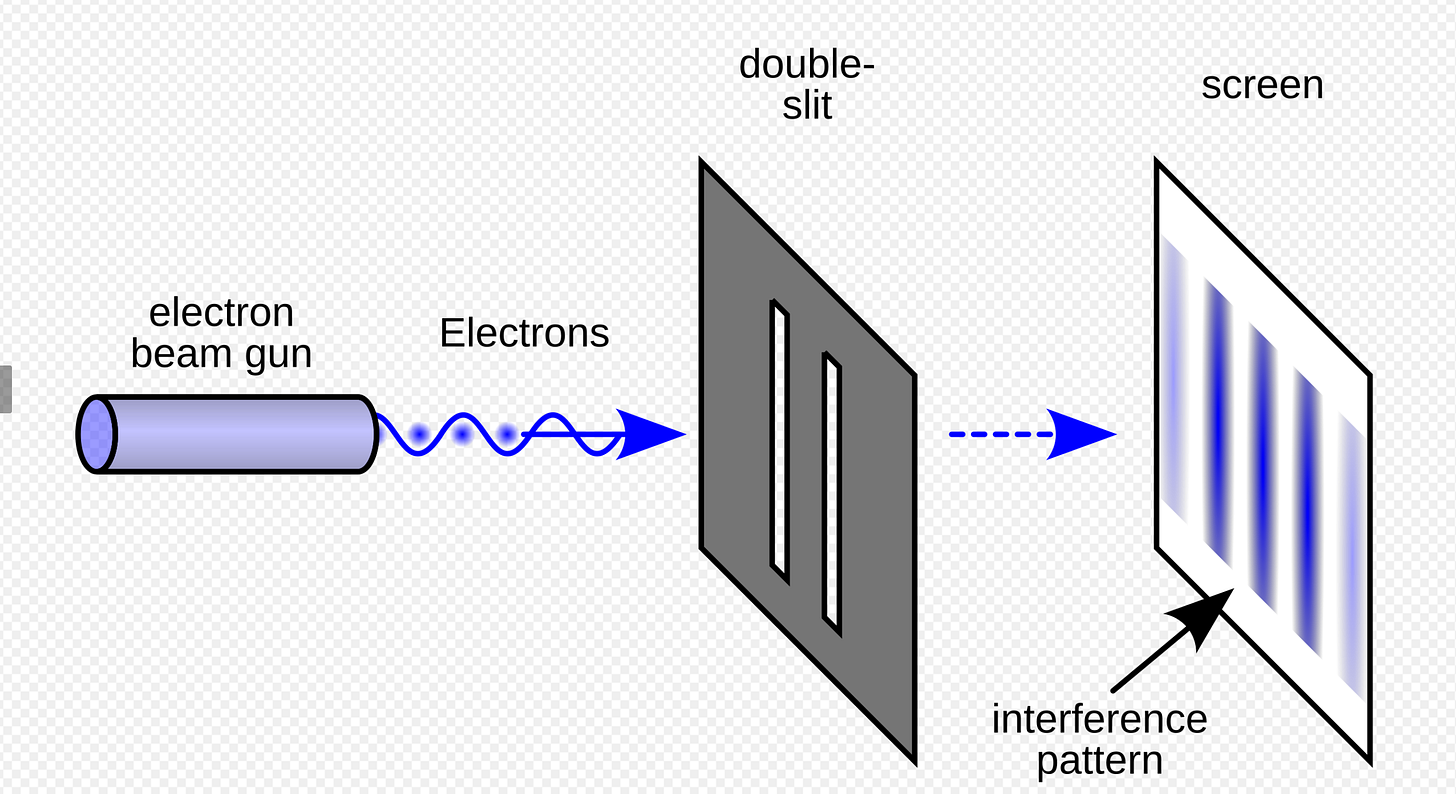

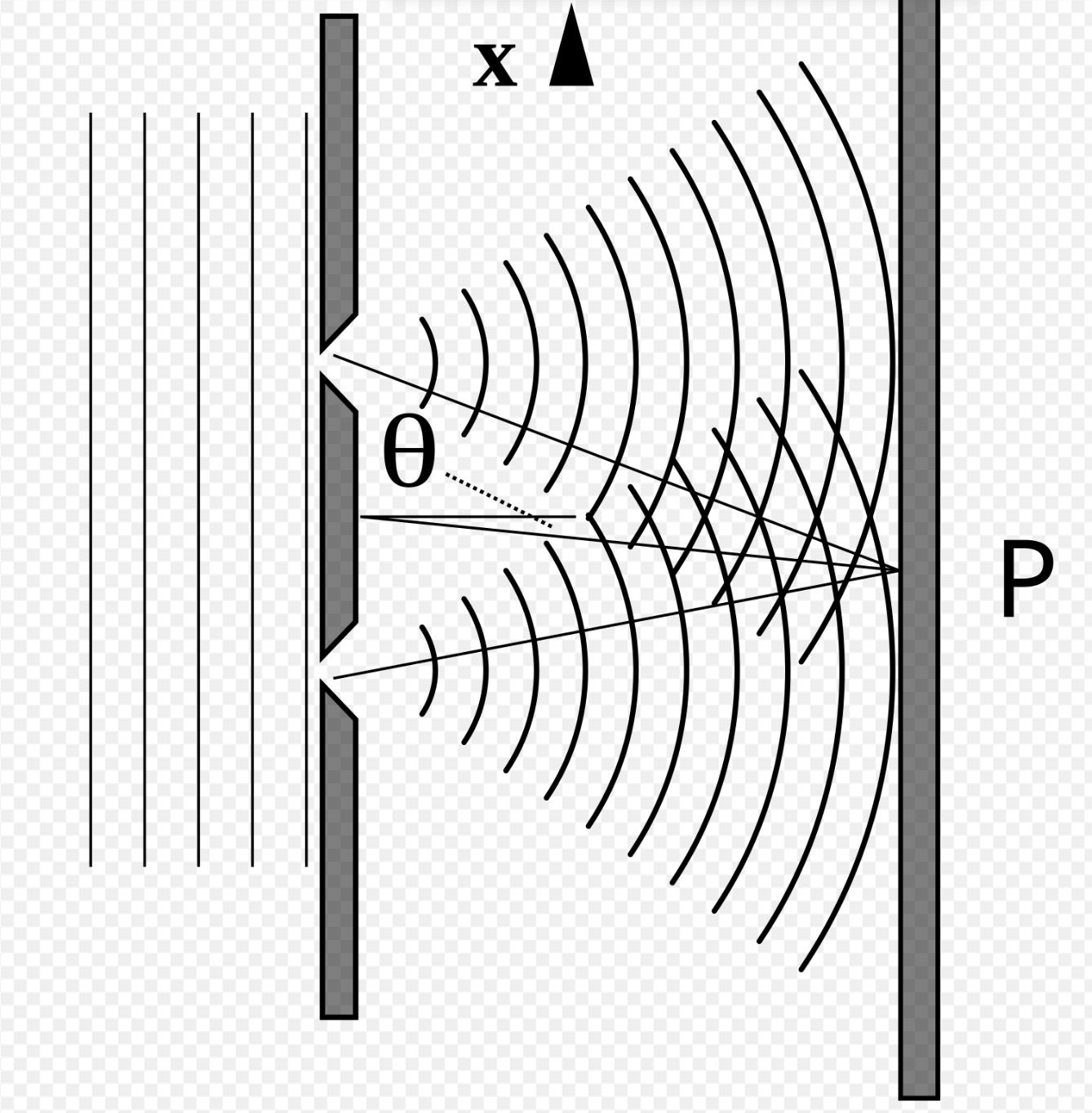

In the early 1800s, Thomas Young conducted what is now one of the most iconic experiments in physics—the Double Slit experiment—and demonstrated that light behaves like a wave. To understand the Observer Effect, you first need to grasp this concept.

The setup? Quite straightforward:

A beam of light

A double slit

A screen to record where the light lands

Young beamed light through the slits and onto the screen. You’d expect two bright spots if light were made of particles, right? But instead, he saw a pattern of alternating bright and dark fringes—classic interference, the hallmark of waves. This cracked open a new way of thinking and nudged science toward what would later be called quantum mechanics—a realm where Newton's rules didn’t quite apply.

Then, in the 1900s, Niels Bohr upped the ante by suggesting light isn't just a particle—it’s also a wave. Later experiments confirmed that even electrons (tiny bits of matter) showed this same wave-particle duality. It was as if the universe had a secret double life.

The Catch

Here’s where it gets funky.

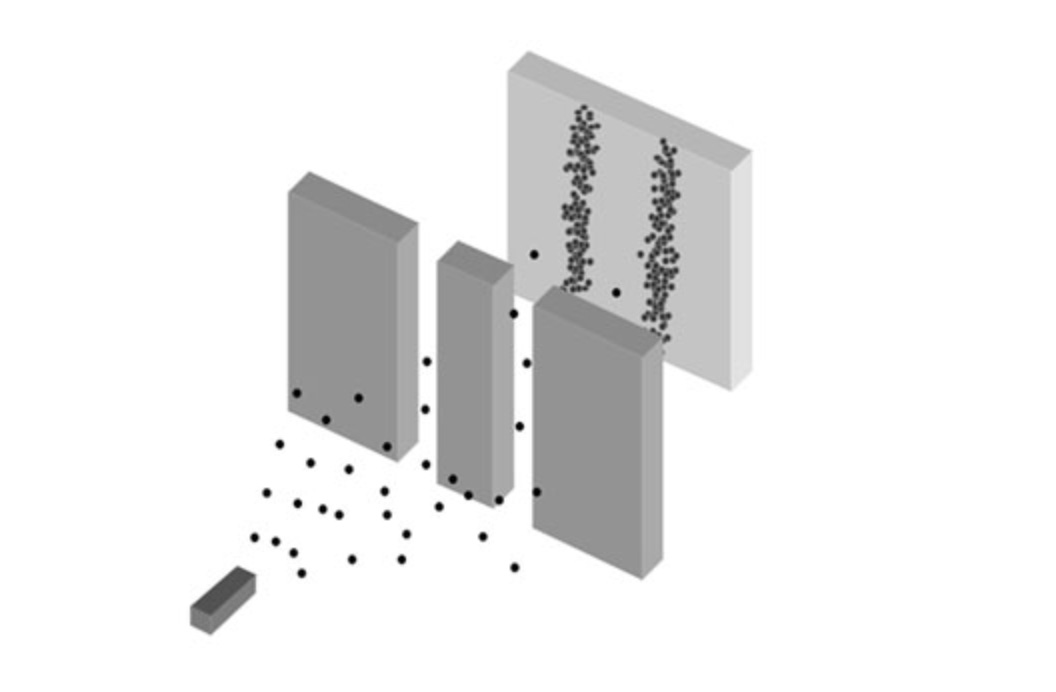

So, originally when scientists passed light pulses through the two slits, the original expectation was that light particles would pass through the slits and land on the screen micmicing the patten of the slits, something like this.

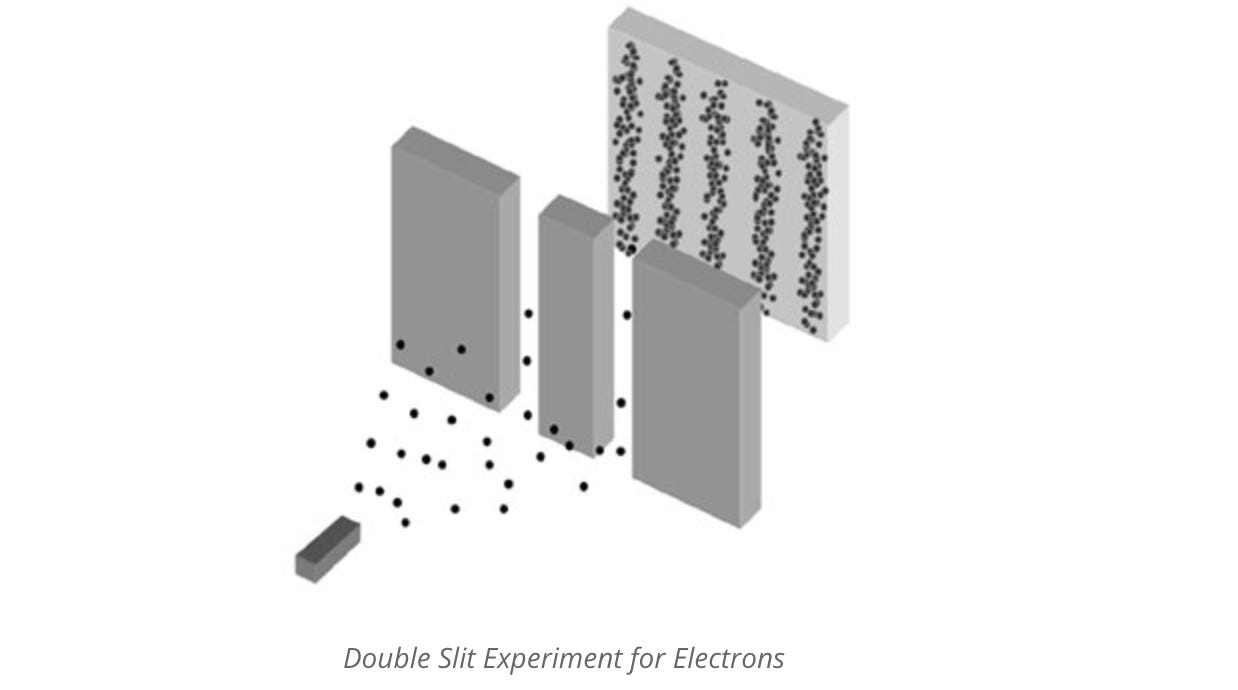

What they found was this interference pattern, something like this:

And again and again they got that same wavy interference pattern, as if each photon was interfering with itself. Wait, what? This meant the photon somehow went through both slits at once, behaving like a wave, and then interfered with itself on the other side. Wild.

The only explanation for the particles travelling across and creating an interference pattern like the one observed above is due to the wave nature of light. The explanation first provided by Thomas Young, suggested that if particles where depicting wave nature they would be passing through both slits at the same time, creating two new wave functions which would constructively or destructive interfere with each other resulting in the bands of light and darkness on the wall as observed in the picture 2.

This experiment has been done hundreds of times since, even with just one photon at a time, and the interference pattern still shows up. It's like the universe knows you're watching or (maybe) not.

The ‘Real’ Catch

Now buckle up. Scientists got curious—what happens if we watch which slit the photon goes through? So they placed a detector at one of the slits. And just like that, poof! No more interference pattern. The photons started behaving like good little particles again, going through one slit or the other and landing in two neat bands.

Then they removed the detector. Boom—interference pattern came right back.

Even spookier? In some versions of the experiment, the decision to observe was made after the photon passed the slits—and still, the outcome changed. Somehow, observing (or not) seems to decide whether the photon behaves like a particle or a wave. The prevailing theory is that observation collapses the particle’s wave function. It forces the photon to “choose” a definite path instead of existing in a fuzzy both-slits-at-once superposition.

If you observe the photon, it behaves like a particle. If you don’t, it behaves like a wave.

The realisation that observing something can alter its reality is what truly is “The Observer Effect”, and it shows up almost everywhere beyond just the quantum physics labs, but in studies of philosophy, psychology, alternative medicine, and even religion.

The Everyday “Observer effect”

The Observer Effect isn't just a quantum experiment—it’s how we grow as people. When I reflected on what I was reading, I could see it everywhere in my life. I realised that what we choose to observe in ourselves changes not only where we go but how we remember where we've been.

For a considerable stretch of my adult years, the period between 2015 and 2017 stands out in my recollection as a time etched with struggle, affecting both my professional pursuits and my well-being. Yet, by consciously adopting a different vantage point, I have begun to perceive that same era through a vastly transformed lens. I now recognise the intrinsic worth nestled within those hardships, the enduring bonds of friendship that were forged, and the nascent self that was in the process of becoming. This intentional shift in my focus has effectively rewritten the chapters of my past, casting a brighter illumination on my present understanding. The way we choose to gaze back upon the tapestry of our lives represents a form of self-observation, and this very act influences the direction of our onward journey.

If you are a movie fan from the 1990s, you have heard about the famous Jim Carrey interview, where he explains about a time of writing fake $10M cheques to himself, visualising his success every day. By 1995, he earned exactly that amount for Dumb and Dumber. This principle is mirrored in the Law of Attraction. Think of it as: what you think about, you bring about. While books like The Secret dramatise this, there’s some truth in the idea that our focus shapes our path.

A thought experiment: spend a month obsessively thinking about 1 problem: writing a book, launching a startup, or learning a language. Maybe, you’ll start seeing ideas, people, and opportunities aligning toward that goal, just maybe…

Final Thoughts

In many ways, the Observer Effect reminds us that we’re not just passive players in this world—we're active participants shaping the narrative. Some physicists and philosophers go even further: they say that the universe is observing itself through us. That our consciousness, our ability to reflect, focus, and change course, is the universe’s way of becoming aware of its complexity.

And maybe that’s why all of this matters. The act of observing—our intentions, our choices, our struggles—changes what’s possible. In our rush to land the next job, get the next promotion, or hit that next milestone, it’s easy to lose sight of the bigger experiment. But what we choose to focus on—personally, professionally, even spiritually—alters not just the outcome, but who we become in the process.

So maybe the goal isn’t always clarity or perfection. Maybe it’s attention. Maybe it’s showing up, watching closely, and letting the observation shape the path. Whether it's photons in a lab or people in a startup or a mid-life crisis, one truth remains: what we observe, we change.

Pranjal, thank you for this piece, I look forward to reading more of your work. "What we observe is not nature itself, but nature exposed to our method of questioning." -Werner Heisenberg

This is so profound. Also, reminded me of the quote I read somewhere, “No phenomenon is a real phenomenon until it is an observed phenomenon”.